Palestinian Weddings are No Joke

Letter #39: Now I'm obsessed with 24 karat gold and a not-so-fun-run-in with the IDF.

5/27/23

Palestinians go all out for their weddings. Kathy told me there are 7 days of parties leading up to the actual wedding date. And pretty much all of them are split up by gender. The bride and groom are celebrated separately by friends and family. At the end of the official wedding night (typically held on a Friday), after dinner, the groom enters the women’s party to see his bride. His father and brothers accompany him.

It was hard to wrap my Western brain around this—the wedding celebration, the bride, the groom…are SEPARATE? Yes. The reasoning behind it I’m not totally clear on. But I know many traditions in Islam have men and women operating separately from one another in public spaces. What I did witness, however, in light of this, is that the men and women have super strong bonds within their gendered communities. While Kathy is Yasmin’s mom, Yasmin has several aunties that are so close to her they treat her like she were their own daughter. Even I was treated like that! All of the women were so warm and mothering to me, it was a wonderful feeling after traveling solo for the previous 3 months.

And while having family super involved in your personal life may feel a bit…suffocating…at times, I could also see the benefits of how close all these family members are. There are so many unspoken codes of conduct that I had to directly ask Kathy or Yasmin about just to understand. (Like choosing a life partner—the family is very involved in that decision-making).

We were attending a wedding of one of Yusra’s family members that Friday evening. Kathy suggested I dress in a traditional thobe, and I jumped at the opportunity to get dressed up and fit in with the crowd.

I wore one of Yasmin’s beautiful thobes, and she helped me fasten a scarf around my hair with a magnetic pin that secured the scarf beneath my chin. They offered up 24K gold jewelry from their collection for me to wear. The gold is SUPER bright, much brighter than what we are used to seeing in the US, some of the pieces passed down from generations before. At the time, I had no idea of the monetary value of the gold I was wearing until the aunties informed me later—it was worth much more than anything I’d ever worn in my life. Palestinian women take their gold VERY seriously.

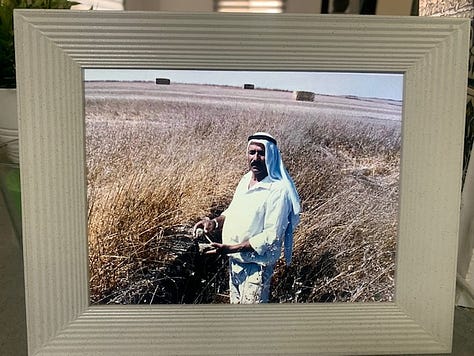

Kathy had told me that Grandma literally spun wool into gold. She’d embroider dresses, weave rugs and goat-hair tents, and turn around and buy gold with her income. She used half her gold to build her house in Laqiya. Such a strong, entrepreneurial woman in the Bedouin community.

Gold jewelry is given to the bride from both sides of the family, including from the groom. Gold can also act as a sort of financial security for the women, so, again, gold is NOT taken lightly. 24K gold is the purest gold you can buy, mixed with no other metals.

Tawfik dropped off the 7 of us women that were attending the bride’s dinner, and he headed to the groom’s dinner. The women in the wedding were all dressed so beautifully in elaborate gowns or thobes, rocking their gold. The color of their hijabs often matched their gowns, and tightly framed their elegant faces, giving a hint of a full bun of hair beneath the scarf. Even the toddlers and young girls were wearing poofy, sparkly dresses and full faces of makeup. I asked Kathy if weddings are ever burglarized, because any robber would make out like a king. She said sure, but rarely, as there is an unspoken rule among Palestinians not to steal from one another—especially the women’s gold. If a family is in need, that gold from another’s family may be the very thing that could help you.

We got some stares as we entered the wedding—I must stand out in an entirely Palestinian crowd. And word travels fast here. Within a day of my arrival Kathy told me EVERYONE in the village, and even the surrounding villages, knew of my visit. You would never experience that in NYC where you can be completely anonymous even in your own apartment building. 😂

But, again, there were perks to having the entire village aware of my presence. The guy at the grocery store insisted I take a free drink as a welcome gift. The guy at the sweets store gave me an entire plate of free knafe. And when I went to get a shellac manicure at Sister’s Salon in Laqiya? She wouldn’t accept payment for the service. She said I had a kind spirit and she was just happy to have me in her salon.

I felt a certain protection when I went on runs along the village fields. The neighborhood kids waved hi when I passed the school, and cars would honk as they drove by, knowing I must be the American staying with the Abu-Saads.

So, at the wedding, even though our entry gained some stares, they were friendly, inquisitive stares, and I was welcomed with open arms.

Many of the younger women danced along with the little girls in the center of the outdoor venue, the DJ blasting Arabic electronic dance music. My family hung back at the table and people watched, greeting neighbors and other family members as they passed by. After about an hour, some women from the bride’s family began serving huge platters of Mansaf (lamb and rice) to every table. A few other things that are different about the weddings in Palestine vs the US? There is no official invitation and no RSVP. The bride’s family has no idea how many guests to expect, so they plan to host A LOT. And, although we were at a third party venue, the entire wedding’s food and drink service was conducted by female family members. No caterers, no booze, no bartenders. But all the Coca-Cola, Fanta, and water you can drink.

The women cook a HUGE vat of this lamb meat and rice meal in a pot called a gider, using a large slotted spoon (called a maswata) to stir and serve onto huge platters. We ate the mansaf from a communal plate. The meal is set in the middle of the table and we rip off pieces of Saj to grab at the meat and rice.

The unfortunate part about no RSVP list is there is likely a lot of uneaten food when the wedding is finished.

We stayed for a few hours and then headed home to hang out with Grandpa before the final call to prayer came right before bedtime (around 9:15pm). He wanted to see me in the thobe, so I waited to change into my comfies. I could see his face light up I entered the room in the traditional Palestinian dress—it must be a trip down memory lane for him to see the women of his family dressed in these thobes, as well as seeing his distant American relative enjoying and participating in his culture.

The following day we had another big barbecue for the family. Ismael had just purchased a super nice gas grill, so Tawfik and Musa loaded it up with kebabs, beef steaks, chicken drumsticks, lamb chops, and veggie skewers. The lamb chops quickly became my favorite dish from these barbecues. There is just SO much delicious food—of course another highlight for me being Yusra’s homemade salads. 😍

After we finished eating we lounged around chatting and sipping on small cups of Arabic coffee. Around 2:30, people began peeling off for the afternoon siesta.

Earlier that week (Tuesday), I had accompanied Yasmin to the Ben Gurion University of the Negev in Beer Sheva. She’s TAing there and just started her PhD. She shares an office with my uncle Ismael, who’s been a tenured employee at the university for nearly 25 years. Yasmin and I had coffee at their favorite campus coffee shop—Aroma—and I worked on my newsletter while she attended meetings.

The following week we’d be heading to Jordan, and the weekend after that we planned on a day trip to the West Bank and another to Jerusalem.

On the first Friday after my arrival, on April 27th, Bilal, Adam and myself had plans to go for a run near the village. I was expecting about a 4 mile run (my usual distance), if I wasn’t too out of shape after sitting around during the meditation course. We started out, Bilal leading the way since it’s a route he takes often. We ran down a gravel road past the newly built elementary school just outside the village. We passed by fields where shepherds graze their sheep and goats. A couple high school students rode their horses down the same gravel path we ran on. We had to walk through some weeds that led up to the highway, where we would then cross over a roundabout to reach the fields on the other side. The dirt roads zig-zagged all over and we had our pick of a route. Bilal said we were so slow we were basically walking (not really an insult but truth coming from someone who’s ran the New York City Marathon three times). Our plan was to run towards the wall that separates the West Bank from Israel. The Apartheid Wall of racial segregation that keeps the Palestinian residents in the West Bank as second class citizens—or worse.

“But isn’t the wall so far away?!” I asked. We had driven past it in 2018 when Hilary and I had visited. Ismael drove us to the checkpoints at the wall so we could better understand the dire situation of Palestinians in the West Bank. West Bank residents that wish to cross into Israel must acquire special permits. It is not easy to find high paying jobs in the West Bank where resources, exports, and opportunities are limited and cut off from Israel and other countries. So, in order to support their families, some residents must work in Israel. But they cannot drive their cars into Israel. They wait in long lines at the checkpoints to be questioned, interrogated, searched, and harassed—sometimes for hours—in order to pass into Israel where they then need to find rides to their jobs. It felt like the people are being caged in, with the checkpoint process being grueling and sometimes humiliating. We did not visit the Gaza Strip, but from what I understand it is much worse—these residents are rarely permitted to leave at all. They are under constant surveillance by land, sea, and air. There is no outlet, extremely limited access to outside resources, and frequent air raids by Israeli militia.

Palestinians living in the West Bank can’t have Palestinian passports because Palestine does not have a recognized government outside of Israel’s control. But Israel will not grant Israeli passports to West Bank Palestinians. So what if an individual wants to travel outside of their country? Well, then they need to find a way to acquire a Jordanian passport. Ok, no big deal, right? But Israel holds the land that these Palestinian families have owned for many generations, and keeps them locked up behind that wall in a seemingly hopeless situation.

Bilal assured me the wall wasn’t too far from where we ran, so I agreed on the condition that we would walk back after—otherwise we were looking at over a 10 mile run. We ran past artificially planted forests of imported cypress and pine trees that were planted over remnants of the villages burned to the ground during the 1948 Nakba—you could still see the stone foundations of homes among the trees. This artificial forestation by the Israeli government would further ensure Palestinians could not return to their homeland—they are now allowed to occupy less than 3% of the land that was once Palestine (within the occupied territory of Israel). It is eerily similar to how Native Americans were ripped from their land by European settlers in the fifteenth century, and later forced onto reservations representing a fraction of the land they once held.

We had one final field to cross before reaching the wall. I asked Bilal if it was safe for us to cross the field instead of using the road—he assured me it wouldn’t be an issue, he runs this route all the time. It was a beautiful spring day, the sun peeking out of the clouds, a light breeze rustling the wheat growing in the fields.

Bilal and I reached the fence that guards the military road just in front of the wall. Ugly snarls of barbed wire line the top of the fence and the wall, a menacing reminder that Palestinians are unwanted citizens in their own land.

We chatted a bit about the wall’s history when we heard Adam calling out to us—in Arabic so I couldn’t understand what he was saying. Bilal signaled for him to come to us, but Adam stayed back, waving at us to retreat from the wall. We began walking back to where Adam stood in the field when we saw the Israeli soldier (IDF) with an assault rifle slung across his chest. He spoke with Bilal and Adam in Hebrew, again I couldn’t understand what they were saying. But I knew we were in trouble by his tone—he did not want us near that wall. Bilal turned to me to ask if I had my passport on me. I feigned searching my pockets—of course I didn’t have it on me! I was in workout clothes and was going for an outdoor run! All I was wearing was an old Apple Watch that was a hand-me-down from Bilal. Since I was running with these guys who’d lived their entire lives here, I didn’t bother to bring my phone or ID. I could tell the soldier wasn’t happy, and wasn’t sure what to do with us. Two Palestinian men and an American woman near the Apartheid Wall. We didn’t even see him coming! And I was confused because we hadn’t done anything wrong…

He spoke with Bilal and Adam a while. Luckily Adam had a photo of his ID on his phone, so he showed the soldier. It was such a tense exchange, but eventually he sent us on our way, our tails between our legs. He followed us a ways, and as we walked I said “well now I know I need to have an ID on me while I run here.” The soldier responded in English “this is NOT a good place to not have ID.” That is, at least for Palestinians or Americans WITH Palestinians. I’m ashamed to admit this but I wasn’t too concerned about the situation, being a white American woman. And I fully recognize the privilege I have, that that is immediately where my mind went. Like, ‘we’ll be ok because I’m with them.’ Surely, I thought, the soldier wouldn’t go after an American—we’re the Israeli government’s best friends.

We began to lightly jog back towards Laqiya, about 5 miles away. Bilal was speaking in rapid Arabic on the phone with Tawfik, Adam’s dad—I couldn’t tell if we were out of the weeds yet. We didn’t turn back to see if the soldier was following us.

Bilal ran ahead of us Adam and I, saying he was going to find Tawfik, who was driving through the fields in his car. Adam said his dad was coming to pick us up. He explained that it was better to get out of there and head back home, rather than risk the soldiers changing their minds, coming out again and picking us up for questioning and detainment—which happens far more than we hear about in the US.

It wasn’t until we got into Tawfik’s car that Bilal said Adam was the one that saved us. The soldier had told them that, when he’d first only spotted Bilal and I near the wall, he was prepared to use a stun grenade to stop us. But he spotted Adam, and approached him first to question him. Thankfully, Adam had that ID on his phone.

This new revelation made me quiet. My American whiteness wouldn’t make a difference in this part of the world—the IDF was not happy about who I was visiting there.

I was momentarily freaked out, because—no—I’ve never experienced that before. And at the same time I was grateful that I now had a first hand experience of what my family has been battling for years, being made enemies in their own indigenous land.

It was not the first offense I witnessed. Things as dumb a being denied a nail salon appointment because of the last name we gave to make said appointment, the salon owner serving up some serious attitude. I faced questioning at the border crossing from Jordan back into Israel, and again when I passed from the West Bank into Israel. Why would I be with family with an Arab last name?, they asked. What possible relation could there be? The rebellious part of me wanted to mess with these interrogators, but I knew I couldn’t. I played along, kept a smile on my face, and stayed aloof. But to know that this is what my family puts up with on the daily…it’s hard not to hate this place.

And this is why I could understand how lovely it was for my family to spend time in Jordan and the West Bank—to be accepted and welcomed there.

The story of Palestine is not my story. It is not my generational trauma. And yet this family I have grown so close to over the past few years—it is their story. As much as it hurts my heart to say this, I get to run away from it. I get to leave, go back to the US where I live a privileged life, free of oppression. No one messes with me because of the color of my skin, and I can move freely through this world because my nationality aligns with the status quo. But as I fell more deeply in love with my family’s Palestinian culture, so also should I share the stories of what I experienced and of what I’ve witnessed while visiting their homeland.

MORE INFO:

It has taken me YEARS to understand what happened/is happening in Palestine. I feel like I almost fully understand it now, but only because I spent an entire month living in that village and asking a million questions. But, for us back in the US, we don’t get the same perspective from mainstream media. Kathy has been sending me news articles of the reality of what is happening over there since 2018, and I STILL needed to experience it firsthand in order to undo what I’ve heard through US media all this time—the Zionist perspective. And, so, with the help of Kathy, I am sharing some articles that are told from Palestinian voices, speaking from their own life experiences. These sources create balance by providing access to voices that are largely excluded from the dominant “mainstream” narrative. My hope is, that if you’d like to further educate yourself on that part of the world, this is a great place to start. And, now that I finally understand it, I LOVE talking about it. So hit me up. Schedule a time to meet by clicking on the Calendly link below and we can talk more.

This organization Institute for Middle East Understanding (IMEU) is very good at conveying Palestinian experiences. I also like their podcast a lot (usually 20 minute episodes) called This is Palestine.

https://imeu.org/article/quick-facts-the-palestinian-nakba

Summary of Israeli Human Rights organization report recognizing Israel’s governance as apartheid:

https://www.btselem.org/publications/202210_not_a_vibrant_democracy_this_is_apartheid

Another report from Israeli human rights groups, including IDF former soldiers in the group Breaking the Silence, and Physicians for Human Rights:

https://www.breakingthesilence.org.il/inside/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Exposed_Life_Evidence_ENG.pdf

The oldest Palestinian human legal rights organization:

https://www.alhaq.org/advocacy/21510.html

Hey! Would you like to connect over creativity, self-growth, and problem-solving? Or just to have a virtual glass of wine or mocktail? Please book a time on my Calendly for us to chat! I can’t wait to see you. XOXO.

If you’re enjoying On the Road, please share with others who you may think would enjoy as well! As always, I love reading your comments and feedback. If you're not already subscribed, please click the button below so I can continue sending you weekly-ish stories and lessons while I travel. 🚙

Your best piece yet - fascinating!

I think you beautifully expressed your experiences and our experiences of life here ❤️. Thanks 🙏🏽